FlamGIRLant

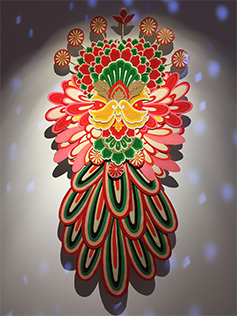

Mayumi Lake, a photographer who teaches at the Art Institute of Chicago, wanted to do something other than print on sheets of lovely paper and then handle them with white cotton gloves. To liberate her work from traditional photographic output—and ways of seeing it—she decided to cut and tear the paper and play with layering and dimension. Lake is also an inveterate collector of vintage kimonos—especially those that are worn to celebrate the rite of passage of young girlhood in Japan. She told me she used to find them at flea markets in Kyoto, where her parents live. But those kimonos are hard to come by these days.

![]()

In her show “Unison” at the Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery in Chelsea, Lake’s pieces combine the sublime with kitsch. Scanned and printed from the nearly extinct garments, typical pastel-hued kimono motifs like chrysanthemum petals and leaves are extracted to become pop-sized elements, carefully placed in loose wreaths, and adorned with pink fur, plastic balls, wig hair, imitation gold leaf, faux sushi grass and neon flowers one could find in a 99-cent store. The yield is a bouquet of vibrant, tactile collages that pop from the walls (spattered by light shards from a disco ball above). Lake’s show is a humorous and reverent celebration of the ephemeral natures of vintage silk kimonos and girlhood.

In her show “Unison” at the Miyako Yoshinaga Gallery in Chelsea, Lake’s pieces combine the sublime with kitsch. Scanned and printed from the nearly extinct garments, typical pastel-hued kimono motifs like chrysanthemum petals and leaves are extracted to become pop-sized elements, carefully placed in loose wreaths, and adorned with pink fur, plastic balls, wig hair, imitation gold leaf, faux sushi grass and neon flowers one could find in a 99-cent store. The yield is a bouquet of vibrant, tactile collages that pop from the walls (spattered by light shards from a disco ball above). Lake’s show is a humorous and reverent celebration of the ephemeral natures of vintage silk kimonos and girlhood.

![]()

Backdrop for a Town Hall Meeting

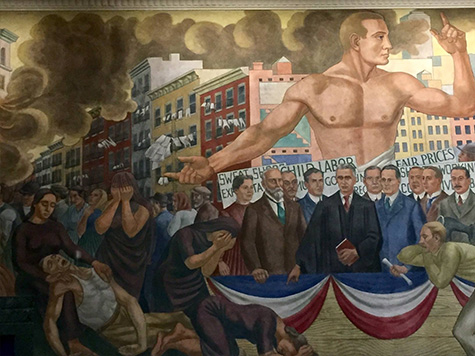

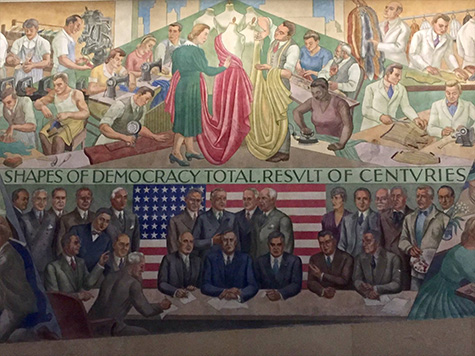

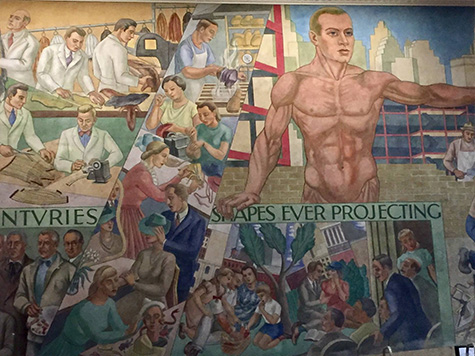

So honored to be represented by Congressman Jerry Nadler, an upholder and scholar of the Constitution, a man of integrity, intellect, and commitment, and an unabashed progressive, who hopefully will be our next Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. Nadler hosted a town hall meeting tonight. He picked the “largest venue” for his constituents, the auditorium of the High School of Fashion Industries on West 24th Street.

The place turned out to be a hidden gem (of many in the greatest city in the world.) There, flanking both walls of the auditorium were two monumental, detailed murals (a WPA project most probably,) completed in 1940 by Ernest Fiene, who depicted the birth of the union movement in the needle trades, emanating from the catastrophic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire.

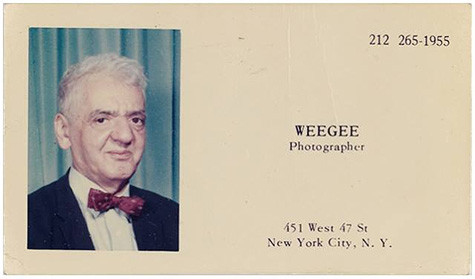

Arthur Fellig in Color

Among the many gems in this trove (332 pieces) of artistic (Sudeks, Shores, Camerons, Hujars, Muybridges, snowflake microphotographs by Bentley, Blumenfeld’s “Blonde,” Capa’s “Bolshoi,”) industrial, scientific, commercial and legal photographic imagery in the intimate photo auction preview of The Knowing Eye: Photographs & Photobooks at Swann Galleries this week (auction today), I found myself returning to examine this ernest calling card, the tiniest item in the show.

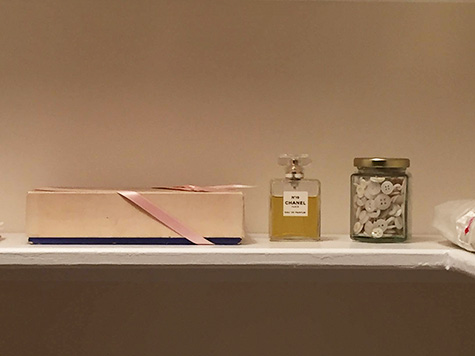

Closet as Shrine

While you’re at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, go see the intimate and ephemeral installation, Sara Berman’s Closet (closing on November 26.) A real closet with real artifacts of the late mother of artist/illustrator icon, Maira Kalman. There is a small wooden bench you can use to sit and reflect, a few feet away. To behold the contents and order of the closet is to contemplate—in more modern terms—the contents of its neighbors at the Museum, royal Egyptians’ sarcophagi.

![]()

I wish this carefully curated and arranged display were made permanent; I would visit it often.

![]()

There is something so sacred and resonant about it. Once Sara Berman’s Closet leaves the Met, it will be traveling, so stay tuned . . .

The Secret Lives of Buildings

Marc Yankus loves the built environment of New York City—as I do,—and his new show, “The Secret Lives of Buildings,” is a paean to the strong silent occupiers of great space in the city. His large format photographic prints of iconic buildings like the Dorilton, Ansonia and Flatiron compel one to contemplate their essence, devoid of commerce, schmutz and motion. They are the silent stoic guardians of the city.

![]()

With an omnipresent perspective (unseen from the street views of mere mortals) Marc also plays with the mundane, portraying some of the unremarkable architecture of Herald Square amidst the scumbled pastel light of overcast days. He considers other micro-neighborhoods, digitally mirroring and collaging edifices,brick textures, and other aging materials. He also isolates the jewel boxes of the city, like the former Parthenon of a bank, now abandoned, that still stands majestically on the corner of 14th and Eighth.

The show—the inaugural exhibit at the freshly painted storefront Clampart Gallery near Madison Square Garden—is for both natives and other denizens of the city—Yankus’ photographs are puzzles to interrogate—we know these dreamlike characters subconsciously, and lingering in front of these portraits, we fill in their contexts and learn their identities.

“The Keeper” Sparks Bodily Joy

According to the popular and best-selling KonMari religion, we are to believe that decluttering—ridding ourselves of things that do not spark bodily joy—will make us joyous and righteous. “The Keeper,” a new, 4-floor show at New Museum provides opposing viewpoints, much more complex in uncovering the myriad reasons and emotional underpinnings of why we collect and how collections give meaning. Displaying thousands of objects spanning the 20th century, “The Keeper” asks us to examine the dissolving boundaries of art creators, curators, collectors, hoarders and preservers. Each individual can be said to be the keeper of their own personal museum.

Clockwise from upper left: Works by Hilma af Klint, Korbinian Aigner, Levi Fisher Ames, and Harry Smith.

Clockwise from upper left: Works by Hilma af Klint, Korbinian Aigner, Levi Fisher Ames, and Harry Smith.

For Swedish painter Hilma af Klint, it was her theosophical musings in the form of a collection of colorful, meticulous oils depicting her own cosmology that she hid during her lifetime. For the priest, pomologist and Dachau prisoner, Korbinian Aigner, it was by painting gouache studies of apple and pear specimens that he could understand and record his experiments of growing them. Civil War veteran Levi Fisher Ames created and toured with his cabinets of personal curiosity, featuring phantasmagorical menageries of hand-sized creatures he whittled from basswood.

Top: Howard Fried’s “The Decomposition of My Mother’s Wardrobe”

Top: Howard Fried’s “The Decomposition of My Mother’s Wardrobe”

Bottom: “The 387 Houses of Peter Fritz”

How does one share a passion of ephemeral discovery? Vermonter Wilson Bentley captured the “tiny miracles of beauty,” snowflake crystals, imaging them with photomicrographs. How do you relive the youthful fun of playing cat’s cradle? Beat artist Harry Smith created collections of string configurations mounting them on simple black grounds. How does one keep a loved one’s memory alive? For Howard Fried, “The Decomposition of My Mother’s Wardrobe” (2014-ongoing,) it is by illuminating the contents of his late mother’s closet, to display, lend and give new life to her by sharing her clothing—not only with museum goers—but with friends who wear and preserve them. For the quilters of Gee’s Bend, the fragments of loved ones’ garments and other remnants coalesce in these iconic commemorative pieces.

What are the roles and responsibilities of the discoverers of others’ collections? Two people preserved 387 models of meticulously built vernacular architecture created by Viennese insurance clerk Peter Fritz that they found in little garbage bags in a thrift shop. Tong Bingxue discovered and preserved 63 annual studio portraits of the distinguished Ye Jinglu, now a photobiography.

Ydessa Hendeles’ “Partners (The Teddy Bear Project”

Ydessa Hendeles’ “Partners (The Teddy Bear Project”

For those who lost family in the Holocaust or survived it, collections are evidence and memory. The heartbreaking denouement of “The Keeper” is the work of a curator, art historian and an only child of survivors. Ydessa Hendeles’ 2002 “Partners” (The Teddy Bear Project) is a two-story library chamber, installed with Escherian staircases, and encrusted with 3000 framed family photographs of people clutching teddy bears—the ultimate metaphor for something that gives us bodily joy and comfort. Even if you have recently created joy from the negative space you have worked hard to create, you will still experience melancholy, sympathy, gratitude, comfort and humanity when you share others’ collections in “The Keeper.” The show opens today and runs through September 25, 2016.

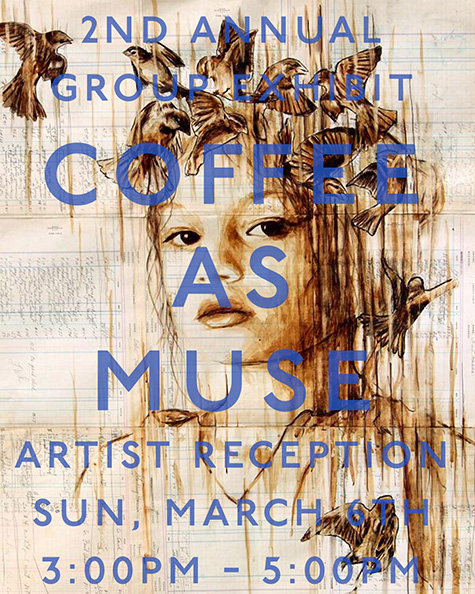

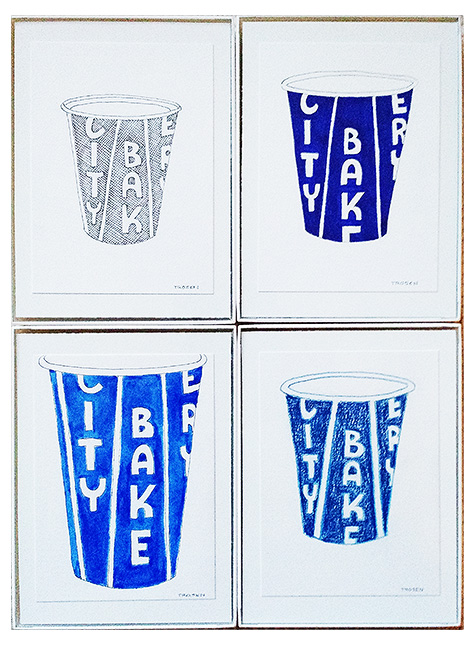

Café Olé!

Like my idol Saul Steinberg, I’m enamored of the beauty of the mundane and practical. Like him, I collect and perennially observe still life items like a paper coffee cup from City Bakery. This particular cup’s softer shade of navy blue, the way the graphics and typography integrate with its stocky form, and the deliberate cutting of the word,” Bakery” are an appealing combination. The cup is a permanent fixture on my table.

So for a new exhibit, “Coffee as Muse,” opening today, I created a series of four postcard-sized portraits of the cup, each in a different medium: cross-hatched ink, pen and ink, watercolor and colored pencil. And I also did a small abstract painting using concentrated French Italian dark espresso.

Forty artists have contributed to this coffee-fueled and inspired show. The second annual “Coffee as Muse” runs from now through April, at No. Six Depot, a café, roaster, art gallery and cultural mecca in West Stockbridge, MA. Come see the show and have a cup of Heart of Darkness with an orange olive oil muffin.

Shot on (My) iPhone 6

![]()

I’m excited and honored to have four pieces in iMotif, a juried show of iPhone photographs in square configurations. The exhibit features the work of 75 photographers and some 350 10” x 10” framed prints.

For me, the winnowing process was a challenge; it took a long time to review hundreds of images I took on the iPhone, honing the final selection down to merely 12—the maximum entry for this juried show. Should I go for scenes of nature? Urban palimpsests? Still lifes?

Originally, five photographs I entered were selected, but HRA (below) taken on West 13th Street one morning did not print as well as imagined.

The other four images also capture the flavor of micro neighborhoods, down to the block. Houston Street is almost a trompe l’oeil image of a layers of posters on a wooden gate impaled by a chain. West 22nd Street, a tableau of a Chelsea dog-sitting parlour, took on the feeling of a dreamlike shrine. Columbus Avenue was caught one morning on a corner at 107th Street, just as school was starting or startling! New Whitney was snatched at one of the openings for the new building.

![]()

The pieces—two and two—are on display at two locations: Sohn Fine Art Gallery in Lenox, MA, January 23 – March 21, 2016, and the Gallery at Hotel on North in Pittsfield, MA, February 2 – March 2, 2016. The photographs are signed, framed and for sale in editions of ten at the Sohn Gallery.

Rosen @ Room & Board

Through yet another moment of managed serendipity, I now have the opportunity to share my work with a national audience. Home furnishings retailer Room & Board has launched a collection of limited-edition prints I created. The collection is being rolled out in their stores in major American cities, and online. Based on collages I made from elements found on the sidewalks and streets of New York City, the six pieces—Mint, Aisle 04, Seperation, Locally Packed, Pastelotto, and 411—are pop, poster-sized, signed and framed, in editions of 20. Not only are they colorful, but the collage prints are filled with puns and other lingo, waiting to be decoded. If you’ve been contemplating a blank wall for a long time, and/ or are in the market for a modern sofa, please visit your local Room & Board showroom, or shop here.

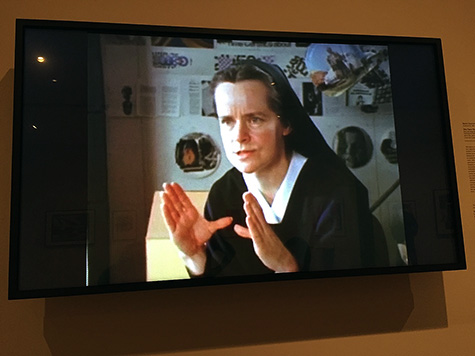

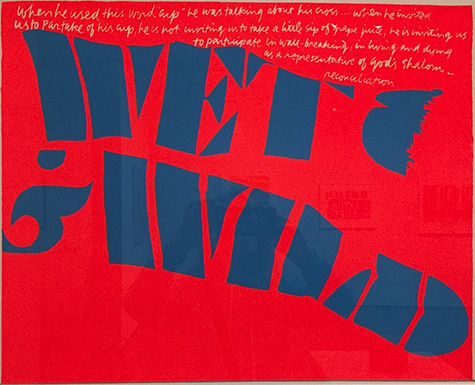

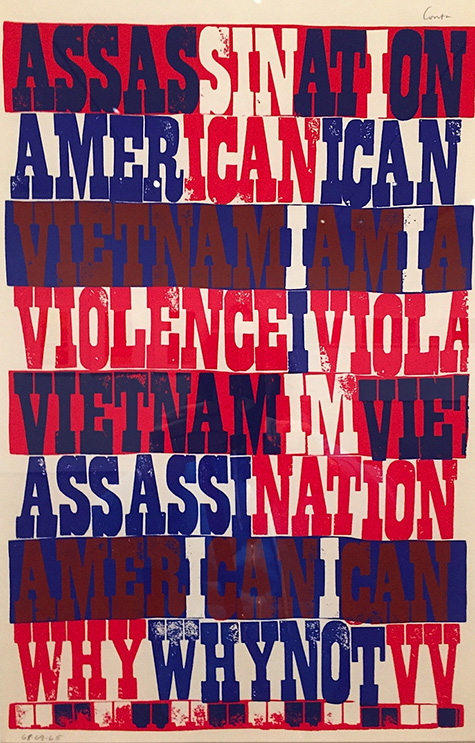

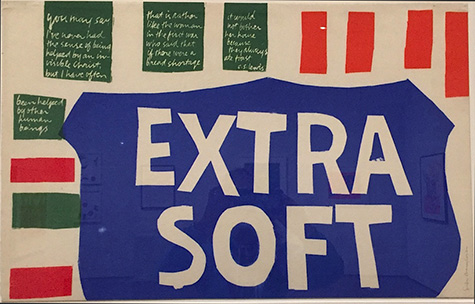

The Sacred and the Pop

Pope Francis would have loved her. Sister Mary Corita Kent (1918-1986) was an alembic—a distiller of the visual, spiritual, intellectual and social, who found and illuminated the spiritual in making art. A Catholic nun, inspiring art teacher at Immaculate Heart College, and social activist, propelled by the reforms of Vatican II, Sister Corita was a pop artist. Her vibrant, graphic silk screened prints of the 1960’s and ’70’s weave popular advertising slogans with the more resonant texts of Daniel Berrigan, e e cummings, Thomas Merton—among others— to produce a body of work that invites closer inspection, and then introspection. The meaning of language she extracted from the commercial realm is exalted in her art.

I made an exhilarating daytrip to Boston to see (before it closes January 3, 2016),

“Corita Kent and the Language of Pop,” at the Fogg. Well-documented, the exhibit features more than 60 of her screen prints, alongside pieces by mostly male pop artists of her time, with some gems by Lichtenstein, Rosenquist and Ruscha.

![]()

Of special significance, on display was a coffee can-sized maquette of Corita’s gargantuan public art icon, the rainbow splashed gas tank outside of Boston. Slide images and videos are powerful testimony to Sister Corita’s social activism in Mary’s Day art be-ins, her art instruction methodology and rapport with students. I wish I could have studied with her.

Of special significance, on display was a coffee can-sized maquette of Corita’s gargantuan public art icon, the rainbow splashed gas tank outside of Boston. Slide images and videos are powerful testimony to Sister Corita’s social activism in Mary’s Day art be-ins, her art instruction methodology and rapport with students. I wish I could have studied with her.